The Uncontrollable Beast: An interview with Russell Haswell and Hugo Esquinca

by Robin Mackay

The following interview comes from the second issue of

Ecoes, a periodic magazine from Sonic Acts about art in the age of pollution. Read this and much more in print by

ordering a copy from our webshop.

Cadáver Exquisito Caleidoscópico en Cuatro Ejes is a new work by artists Hugo Esquinca and Russell Haswell, commissioned by Sonic Acts. The work incorporates the game of ‘exquisite corpse’ – a technique of collective assembly in which participants take turns contributing to a work after seeing only a portion of what the previous person has contributed. Initially intended to be presented on a live multi-channel system in the Spring of 2021, before its postponement as a result of Covid-19, Cadáver Exquisito is the second outcome of the collaborative approach the artists have developed through a series of virtual residencies. Now reconfigured to binaural audio, the work is available to download and experience in 3D stereo sound. Ahead of the release, Esquinca and Haswell sat down with Robin Mackay to discuss the development of the work amidst the contingency of the pandemic, and how elements of everyday life and current events came to permeate the auditory fragments they exchanged.

Cadáver Exquisito Caleidoscópico en Cuatro Ejes (2021, 35 min) can be downloaded and experienced in 3D stereo sound at

sonicacts.com/cadaverexquisito.

Robin Mackay: You made two versions of your piece, Cadáver Exquisito, during the weird situation that we all experienced in the Covid lockdowns: a lack of living contact and a search for new modes of communication to work around it. Did you both suffer not being able to be out there doing performances?

Russell Haswell: After we finished the first one, we were given the opportunity to do a piece for Sonic Acts on a multi-channel sound system. It was a continuation of the process: each of us would make five-minute sections of audio, share only the last thirty seconds, and then the other one would start from there.

A lot of it is fuelled by the anxieties that have been created by Covid. During the first lockdown, there were no performances or travelling, and both Hugo and I were affected by it. However, we got an opportunity to do a virtual residency with the Goethe-Institut. We did not have to go anywhere; we could just stay at home and have daily chats as if we were meeting at a residency programme. At the time, musicians were DJing on top of mountains, being filmed by a drone, playing to no one; festivals did live streams of the gigs they organised with local artists. We did not want to stream anything; we did not want to do a live gig. The idea of applying the exquisite corpse method gave us the ability to create something different through an internet exchange.

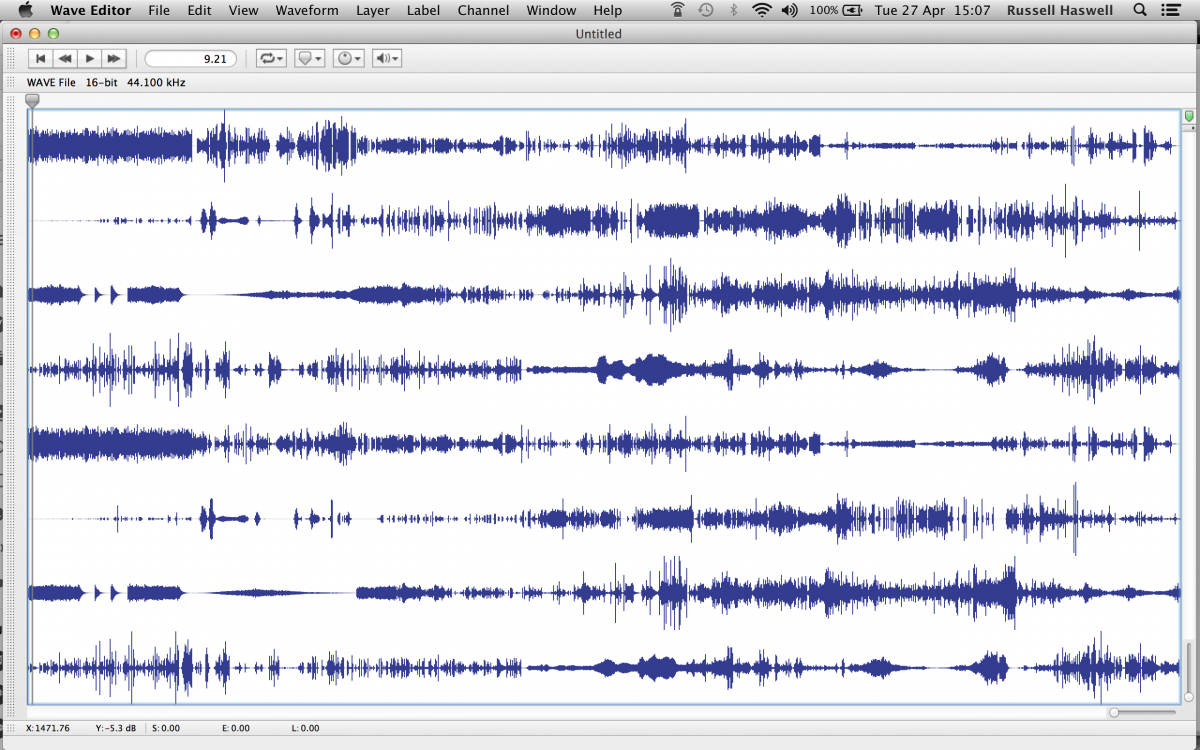

Screenshot of the WaveEditor software displaying eight channels of sound that make up the piece Cada?ver Exquisito. Courtesy of the authors.

Anti-lockdown protest in London, 19 December 2020. Photo by Steve Eason

At the time, we both watched whatever we could find on

YouTube, for example, Photography is Not a Crime movement videos

[1], which led us to Ruptly’s

[2] live feed coverage of the Julian Assange case outside the High Court, the lockdown protests in Hyde Park and in Paris – all in real time. At the end of the second lockdown, we were getting into things like ASMR, pimple popping, euro coin pusher, extreme ear wax removal, cooking, butchery, Anthony Bourdain, Asia Argento, St. John’s restaurant, anti-NFT, the Scottish islands…

Hugo Esquinca: We tried to move away from the idea that collaboration is a form of direct improvisation. Instead, we engaged with possible consequences of constant exchange, but without it having to result in a sound piece.

RM: So, you weren’t just silently passing the audio files between the two of you? You were hanging out in mutual isolation, with common moments, moods, a shared climate?

HE: We never talked about the synthesis processes, or about fetishes around the gear we were using. It was just that everything that was happening around us permeated the slices of audios we were exchanging. Sometimes we would chat and have the live feed of the demonstrations in Paris running on another screen for six hours. At the same time, I went through my archive of newspapers in the genre of Mexican

nota roja, which is an extremely yellow sort of journalism that documents physical violence and crime. All this content informed what we were doing. All this never became a direct reference, and the piece is not really an extension of it, but that dynamic, that overflow of information, was clearly there for both of us.

RM: Is the piece a kind of bearing witness to this short period of history and all those upheavals and public events that were a part of it?

RH: This lockdown was a bit like being trapped in your own pigsty and you’ve got to wriggle around in your own waste for a while… Our daily residency conversation was about contaminating each other with all the stuff we were consuming. It was all new, it was all real-time, it was what was going on in the world at the moment. This constant exchange, this exposure to materials, may have been sublimated into the piece.

Supporters of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange march to London’s High Court ahead of his appeal in his extradition case, 23 October 2021. Photo by Steve Eason.

Supporters of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange march to London’s High Court ahead of his appeal in his extradition case, 23 October 2021. Photo by Steve Eason.

: The piece was surely based on this climate of dread and anguish. I think it becomes a testament, but without the moralising aspect, or sound as evidence of these last years. We are not trying to be didactic about the pandemic, but I think the piece definitely bears witness to the situation. Even our exchange, I suppose, is what makes it a kind of evidence of the circumstances.

RM: You have both been involved in a number of collaborations before, so what was the experience of doing it this way?

RH: This time we were in a bubble together. Obviously, there is something about actually being in the same room with somebody, but, in the end, we did not really have a problem with this. It was really straightforward. And at the same time, it was perhaps a way to deal with loneliness. There was the anxiety of the entire situation, not knowing how long it would go on for, there was the anxiety of the future, the reality and uncertainty of Brexit, which was also a major consideration for people who rely on travelling abroad for their income, fund applications...

RM: You both tend to favour the production of disturbance and uncertainty in your work, putting audiences into a situation where they don’t quite know what is going to happen next. Does it change your practice, being inescapably embedded in a situation of contingency?

HE: The slices of audio that we were sharing always concealed a part of themselves, and that had an effect on our work process. In the cadáver you compose something from whatever you are given and try to take it as far away as you can from where you started, knowing that the other person will do the same thing. It is based on the fact that you will accept whatever the other one is doing without question. In both pieces, we never reviewed what we had done, we only listened to it when it was compiled. There was never an opportunity to say, maybe we should do this part again or leave it out. It was whatever it was.

RM: Russell, you have always had an interest in the concept of real-time, you even made a piece called Recorded As it Actually Happened. You have also used a technique you call ‘artificial worldizing’, where you take real-time recordings and re-record them in another space to make a new, displaced authenticity. It seems like the cadávers extended that interrogation into the lockdown situation by way of a refusal to be real-time.

RH: We submitted to one another’s stream of consciousness because, in fact, we were working together in real time. We just did not generate the end result together in real time. But all of the recordings I made for both pieces were made in real time; I improvised, worked in my usual way, and then forwarded the recordings to Hugo.

HE: I was also working in real time with what I was being sent, but we were never interested in engaging with the idea of the entire process happening for both of us simultaneously. That simultaneity was taken over by the Ruptly live feeds and our live chats, rather than engaging with the practical aspects of synthesis.

There also tends to be some fetishizing about utilising real time within a stream, and that is always related to the problem of latency: how it can play a part in producing what is happening in different places at the same time. The alternative is to leave that aside completely and just try to operate within what is happening wherever you are. That is why I was not interested in having a complete idea of what our piece was until the end. That moment when it is played back is akin to real time.

RM: As with the exquisite corpse, when you unfold the drawing at the end and see the monster in its entirety for the first time. What was that experience like?

HE: The initial plan with the second

cadáver was that we would listen to the piece only on the multi-channel system, without making any kind of stereo or binaural mix. So, this is still just a glimpse of the full picture.

Anti-lockdown protest at Trafalgar Square, London, 26 September 2020. Photo by Steve Eason.

End the Lockdowns, Mayday 2020, New York. Photo by Felton Davis.

is an artist, record producer, free improvisor, computer musician, noise aficionado, and curator. He was trained at Coventry School of Art, graduating in 1991. Russell has focused on the performance and methodology of large-scale sound works, sometimes using surround sound. As a curator, he has delivered projects for PS1/MoMa, All Tomorrows Parties, Aldeburgh Music and Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary. He lives and works in Glasgow.

HUGO ESQUINCA is an instigator in Audio Electronics and Acoustic Interventions. His research as intervention/intervention as research in sound explores different degrees of exposure to thresholds of indeterminacy, spectral de-gradation, erratic processing techniques, and excessive levels of amplification. His work has been executed in different contexts such as Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, National Centre for Contemporary Arts NCCA-Moscow, Fondazione Antonio Ratti-Como, Aalto University-Helsinki, Haus der Kulturen der Welt and Berghain-Berlin. Originally from Mexico City, Hugo lives in Berlin.

ROBIN MACKAY is a philosopher and director of the publisher Urbanomic, which aims to engender interdisciplinary thinking and production. As well as directing Urbanomic, he has written and spoken on art and philosophy and has also worked with a number of artists developing cross- disciplinary projects. Mackay has also translated innumerable essays and various book-length works of French philosophy, including Alain Badiou’s Number and Numbers, François Laruelle’s The Concept of Non-Photography and Anti-Badiou, Quentin Meillassoux’s The Number and the Siren, etc.